This Boxing Day marks the centenary of the death of Private Albert George Cooper [10/380], one of New Zealand’s earliest casualties of the First World War.

Private Cooper, of Hawke’s Bay, never saw battle. Eight days after his arrival in Egypt with the NZEF he was hospitalized, suffering from pneumonia. He never recovered and died on 26 December 1914.

Albert was born in Hastings in 1891, to William and Elizabeth Cooper, of Tarapatiki, Waikaremoana. His occupation on his attestation forms is given as a painter, his last employer S. Sargent, of Wairoa. He is described on enlistment as 5ft 8 inches tall, 126lb, of dark complexion, with brown eyes and hair.

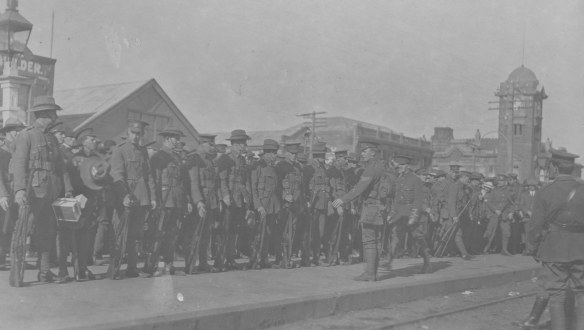

Albert enlisted with the NZEF in the 9th (Hawke’s Bay) Company of the Wellington Infantry Battalion in September 1914 and sailed with the main body on 16 October.

![Photograph of Private Albert Cooper (front left), and three other unidentified soldiers take at Electric Studio, 90 Manners Street, Wellington, October 1914, prior to the departure of NZEF. collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi,[75041]](https://mtghawkesbay.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/750411.jpg?w=584&h=366)

Photograph of Private Albert Cooper (front left), and three other unidentified soldiers taken at Electric Studio, 90 Manners Street, Wellington, October 1914, prior to the departure of NZEF.

collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi,[75041]

O E Burton wrote in The Silent Division impressions of the arrival of the NZEF in Egypt:

The men went thronging into the city. And what a night they had! At midnight they came back to the familiar holds but not to sleep. They had seen marvels and must recount what they had seen. Excited men talked at the top of their voices. No one listened to anyone else. Everyone was too full of his own experiences—and so the babel flowed on. In one evening they had seen Aladdin’s Cave, the Forty Thieves, and the houris of the Thousand and One Nights; veiled women and others whose draperies were of the most diaphanous sort. French, Greeks, Russians, and Italians, with the brown-skinned Egyptians and black Nubians from the south—all these they had seen and the spell of Egypt had taken hold of them.

The diary of Edward P Cox, a fellow soldier in the Wellington Regiment (and who later noted Albert’s death in its pages) wrote of Alexandria:

Saturday, December 3rd

Went ashore this evening to Club de Anglais of which we have been made hon. members. The best quarter of the city is very well built and very fine at night when all lit up as I saw it tonight. But the native areas about 2 miles of which I passed in a cab going to the wharves, have narrow streets, most evil smelling, and cafés, saloons and open bars etc galore. The work of unloading horses & military stores goes on and trains for Cairo leave every hour or two.

Men of the Hawke’s Bay Company were given a half-days leave on the 5th to visit Alexandria, before departing for Cairo on the 6th. In the museum’s collection we hold a postcard, likely written on 5 December, to his sister-in-law Alice Maud Cooper. Maud was the wife of his older brother William Edward Cooper, watchmaker of Napier. In the short note, Albert (or Albie, as he signs off) gives his love to Betty, their daughter, his three year old niece.

![Postcard, from Albert Cooper to WE Cooper, 1914 [front] collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi,75/29](https://mtghawkesbay.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/750401.jpg?w=193&h=300)

Postcard, from Albert Cooper to WE Cooper, 1914 [front]

collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi,75/29

![Postcard, from Albert Cooper to WE Cooper, 1914 [back] Mrs W E Cooper, of 13 Napier Terrace 9 December 1914 Dear Maud We have got as far as Alexandria. We are going to ‘Zeetun’ outside Cairo in Monday. We have leave here today and town is very interesting. Will write and tell you all about it. Love to Betty. Yours etc Albie collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi,75/29](https://mtghawkesbay.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/750402.jpg?w=300&h=195)

Postcard, from Albert Cooper to WE Cooper, 1914 [back]

Mrs W E Cooper, of 13 Napier Terrace

9 December 1914

Dear Maud

We have got as far as Alexandria. We are going to ‘Zeetun’ outside Cairo in Monday. We have leave here today and town is very interesting. Will write and tell you all about it. Love to Betty.

Yours etc

Albie

collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi,75/29

The desert training regime was intense, but outside of their work, the sights of Cairo were an irresistible lure to all ranks. We do not know if Albert had the opportunity to visit Cairo, or see the wonders of ancient Egypt – the Pyramids, the Sphinx on his picture postcard home – before he succumbed to illness.

On the 10th December, five days after this postcard was sent, Albert was admitted to Abbassia Hospital, a British facility, east of Cairo, with pneumonia, along with fellow Hawke’s Bay soldier John Archibald Campbell, driver for Barry Bros of Napier. John Campbell died on the 14th, while Albert remained seriously ill in hospital, eventually passing away on the 26th. Respiratory diseases such as influenza, tuberculosis, pleurisy and pneumonia were rife in Egypt and struck many of the new arrivals from Australia and New Zealand.

We do not have a record of his funeral, but Albert’s death is noted in the diaries of other soldiers in his unit. It is possible that his next-of-kin were cabled with news of his death, and it was widely reported in the New Zealand papers from 30th December. The news must have come as a shock to the tiny East Coast community in which he grew up. His brief postcard from Alexandria, would have arrived in Napier much later and must have been a treasured remembrance of Albert, and his grand adventure, cut tragically short. Thus far, it is the only known letter of Albert’s to survive.

AG Cooper’s grave, Cairo War Memorial Cemetery, Egypt

Private Cooper is listed as aged 26 on his memorial, though he was actually only 23.

http://www.nzwargraves.org.nz/casualties/albert-george-cooper

The museum also holds Albert’s Memorial Plaque in its collections. These were issued after the end of the war to the next-of-kin to all British and Empire service personnel who were killed as a result of the war. The full name of the dead soldier is engraved on the right hand side of the plaque, without rank, unit or decorations. They were issued in a pack with a letter from King George V and a commemorative scroll. These plaques were colloquially known as the ‘dead man’s penny’ because of their resemblance to the penny coin.

AG Cooper, Memorial Plaque

collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi,75/29

gifted by Mr Noel G Cooper

The First World War was the first major conflict in which the overwhelming majority of military deaths were battle-related, rather than caused by disease. Of the 16,703 New Zealanders who died during the war years, 63% were killed in action, 23% died of wounds, and 11% of disease.

♦

Dedicated to the memory of those of the Regiment who gave their lives in the Great War;

And to our fellow soldiers of the Regiment who remain to serve the country in peace;

And to the present and future soldiers of those battalions that made the Wellington

Regiment N.Z.E.F., in whose keeping is its good name.

For us the glorious dead have striven,

They battled that we might be free.

We to their living cause are given;

We arm for men that are to be.

– Laurence Binyon

Dedication from the frontispiece of the Wellington Regiment unit history, Cunningham, Treadwell and Hanna, 1928

♦

Albert’s story will be featured in MTG’s upcoming First World War exhibition, to open in April 2015. His service record is available online at Archives New Zealand, http://www.archway.archives.govt.nz/

Eloise Wallace, Curator Social History

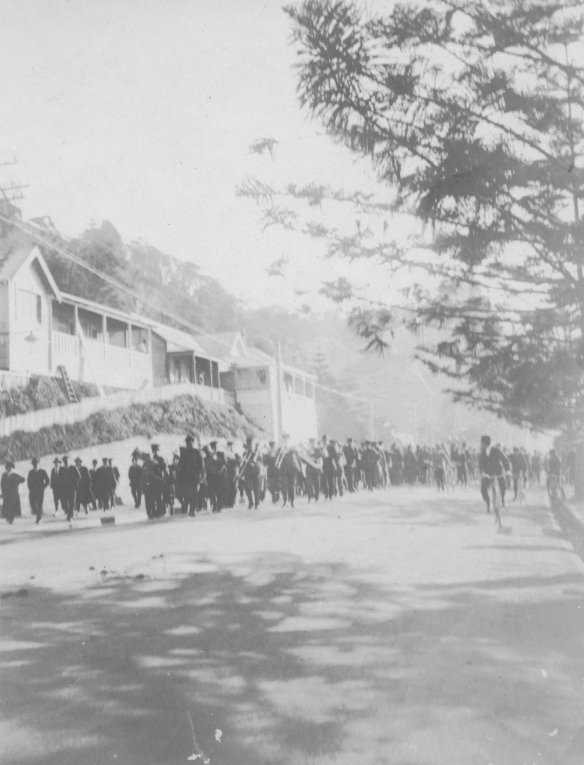

![9th (Wellington East Coast) Mounted Rifles squadron at Awapuni. Collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi, M2004/6/3 [91283], Gifted by Dale Connelley The squadron was commanded by Major Selwyn Chambers (d. 7 August 1915); 2nd in command was Captain Charles Robert Spragg (and possibly pictured on lead horse), with Lieutenants Norman Donald Cameron (d. 30 May 1915), Percy Tivy Emerson (d. 30 May 1915), Arthur Frederick Batchelar, and 2nd Lieutenant Henry Beresford Maunsell (possibly the four men behind Spragg). Chambers may have taken this photograph. The Gallipoli campaign would destroy the original NZMR Brigade. Half of those who served at Gallipoli died, or were wounded. All would fall sick.](https://mtghawkesbay.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/12603.jpg?w=584&h=364)

![Napier Contingent Day ribbon. Collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi, [74627]](https://mtghawkesbay.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/74627.jpg?w=300&h=296)